Safety First

Everything I will be discussing is inherently dangerous. Molten pine resin and beeswax can cause severe burns and care should be taken to avoid damage to self or others. All of the materials are flammable and will be exposed to heat. The materials discussed below should be treated with utmost caution and the methods shown are how I did something, not advice on how you should do anything. The author bears no responsibility for your handling of dangerous materials or any damage or pain that results from your personal experimentation. If you attempt to replicate any of the experiments discussed below, you do so at your own risk. Do not inhale any fumes or dust. Please dispose of any waste responsibly and in accordance with local laws. Stay safe, friends.

Why Wax? Why Rosin?

I spend a lot of time working cloth and leather with linen and hemp thread. Running these threads across a small bit of beeswax is a necessity to condition the fibers, which increases their durability and eases the passage of the fiber through the material. The wax is both conditioner and lubricant. With high-friction materials like leather, thread builds up heat as it is pulled through. Waxed thread will just lightly melt the wax — further embedding it into the flax or hemp fibers — whereas unwaxed thread will take the heat directly and be weakened thereby. In cloth, the waxing seems to help keep the thread from sawing through the laid fibers of the weave, making for a stronger seam.

In shoemaking, there’s the additional concern of stitches being in close and constant proximity to the ground, exposed to mud and water: two things which will rapidly degrade natural plant fibers. Straight wax will protect the fibers for a short time, but to really get things sealed up, resinous tree sap is added to the wax to really glue everything together.

Put plainly (as I understand it) the value is fourfold:

1. Shoes are sewn with boar bristles, which have to be adhered to the threads, and the sticky wax is used for that. More on bristles another time.

2. Shoes are sewn with multiple threads plied together (for strength and as part of the boar bristle process) and the sticky wax helps them combine, holds them together, and conditions them much as beeswax does for cloth sewing thread.

3. There’s a level of stiction created by the rosin, which holds the thread in place in the hole, preventing one broken stitch from becoming a row of broken stitches.

4. The rosin-impregnated wax provides water and rot resistance for the plant fibers, which will be the weakest link in a leathergood that is in constant contact with mud and water and such.

This resinous wax we’ll be making and using is commonly called coad or sometimes code and has come to be referred to simply as “hand wax”, though that seems to be a more modern term to distinguish it from machine waxes (Carlson, 2005).

Considering the confidence with which the assembled minds of historical shoemaking insist that shoemaker’s wax made from pine resin, pitch, beeswax, and sometimes tallow is a necessary accompaniment to any historical shoemaking experimentation all the way back to paleolithic times, I was surprised to read the inimitable Marc Carlson cast doubt on the whole thing pre-1600.

“First, let me state clearly that we don’t know what shoemakers used on their threads during the Middle Ages. It appears to be an article of faith for some scholars (like Pritchard) that shoemaking threads were ‘waxed’, although what exactly is meant by this term in not clear…” I. Marc Carlson, Footwear of the Middle Ages, 2005 (Accessed January 2025)

Carlson goes on to say that the earliest clear indication as to what exactly went into the wax of the shoemaker dates to a recipe first written down in 1813, though the ingredients are alluded to in a 1603 law enacted under James I (quoting from Marc’s footnotes) ‘The Leather Act of 1603/4’ in ‘Statutes at Large’ under James I, sets the legal specifications for shoemaking threads, or “waxed-ends”, as: “…good Thread, well twisted and made, and sufficiently waxed with Wax well rosened, and the stitches hard drawn with Hand Leathers, as hath been accustomed…” (Carlson, 2005)

Since Marc was writing his book in 1996 and hasn’t updated (as far as I can tell) since 2005, it is possible that scholarship in the realm of historical shoemaking has advanced significantly in the past twenty years. Or, it is always possible that this is just Something We Do Because It’s Something We Do, which is frightfully common in these areas.

Thank God I’m not writing about shoemaking in the middle ages; 1603 “…as hath been accustomed…” is close enough for me, so we may carry on with our experimentation into making “Wax well rosened”.

Let us agree to terms…

Here is a glossary of terms as I will be using them because some of these terms have meanings that can vary depending on your geography, timeframe, culture, and seem to shift with the tradewinds. This is not a definitive definition, it is simply what I mean in this article when I use these terms.

I am avoiding the use of “pitch” entirely because it is a confusing term used wildly across our research period to the point where using it at all risks confusion.

n.b. I have included links to the Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) for rosin and pitch/tar because they are the two most dangerous ingredients we’ll be working with today. The MSDS is a good source for ignition temperatures (the “flash point” of a substance) which is important to know when applying heat to it as part of a process.

- Coad: A mix of pine rosin and/or tar with wax, sometimes cut with a light oil or fat to improve handling.

- Rosin/rosen: The dried and condensed sap or resin of certain pine trees. Used for many purposes ranging from increasing the friction of violin bows to increasing the grip of a baseball bat. Generally purchased in large clumps that look like whiskey-flavored rock candy, it is sticky and melts easily, though is also quite flammable.

Pine resin/rosin MSDS: https://www.earthpaint.net/uploads/7/9/8/8/79882642/3d_pure_pine_resin.pdf - Pine tar: The sap of certain pine trees that has been further refined by boiling in a kiln or over a fire, allowing it to thicken as it blends with the carbon from the firewood to form a dark, thick, viscous, tar, often referred to as “Pine Tar” to distinguish it from petroleum-based tar. Pine tar holds its sticky, goopy, state longer than rosin and is also quite flammable.

Pine tar MSDS: https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/2015/7855/files/SDS-Auson-Special-Kiln-Burned-Pine-Tar-773.pdf?v=1705599268 - Beeswax: “(also known as cera alba) is a natural wax produced by honey bees of the genus Apis. The wax is formed into scales by eight wax-producing glands in the abdominal segments of worker bees, which discard it in or at the hive. The hive workers collect and use it to form cells for honey storage and larval and pupal protection within the beehive. Chemically, beeswax consists mainly of esters of fatty acids and various long-chain alcohols.” (Wikipedia)

- Tallow: The rendered and clarified fat of, in this case, a cow, though sheep was probably more common in 16th century England. Shelf stable and paste-like at room temperature, it was a common ingredient used in the 16th century for everything from shoemaker’s wax to cosmetics, it was also commonly rubbed into leather as a dressing and waterproofing agent.

Wax Well-Rosened

Because this is the 16th century and our oldest recipe is just a law saying that wax has to be “well-rosened” we are going to work with that as best we can, at least for the first attempt.

Recipes found on the internet vary wildly from a 1:1 ratio of rosin to wax (usually with a small dollop of tallow thrown in for handling) to 2:1 and up. There’s some variance on whether pine tar is even mentioned and sometimes a distinction is made between white wax (rosin+wax+tallow) and black wax (pine tar+rosin (sometimes) + wax) and, occasionally, someone will say that black wax was medieval and white wax is of the renaissance, perhaps because the description used in 1603 mentioned rosen/rosin and wax, but not any form of tar, which would imply a blacked product (probably… see earlier note about the trouble with tar).

We are going to attempt to adhere to the terms set out by James I and make our wax well-rosened. We will delve into the sticky issues of tar in another post.

By far the most prevalent and reportedly-successful white coad makers on the internet (see resources, below) seem to prefer a ratio of 60% rosin to 30% wax with a dash of tallow, so that’s where we’re going to start.

Mise en place

Equipment:

Kitchen scale

Metal or ceramic bowl-we-don’t-care-about

Measuring scoop

Disposable chopsticks or silicone spatula (we used both)

Tub filled with hot water, about body temperature. (do NOT use your sink, this stuff will NOT be kind to your plumbing)

Ingredients:

2 oz (56g) The finest Georgia pine rosin (in rock form)

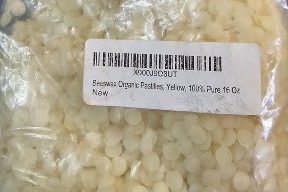

1 oz (28g) Organic, pure bees wax pastilles.

1 smidge of beef tallow (sheep would be traditional, but I could barely find beef tallow. Honestly I don’t see any reason lard or duck fat wouldn’t also work, but I haven’t tried it.)

Recipe:

Preheat (electric) oven to 300° F (approx 150° c).

The recipe is simple: We will combine, by weight, in the bowl-that-we-don’t-care-about 2 ounces of rosin and 1 ounce of pure organic beeswax pastilles (they look like lentils).

Break up the rosin rocks by putting them in a bag and lightly bashing them with a handy rolling pin or pestle. In fact, some people do this with a mortar and pestle, but I didn;t have one handy that I wanted to sacrifice to the cause, so we went with the bag-and-bash method.

The bowl of rosin and wax was placed on a cookie sheet in the center of our preheated electric oven. (I stress electric because of the previous discussion about flammability and flash points. An open flame just seems like a bad idea.)

n.b. I put a silicone mat underneath to catch any splashes or drips. Baking parchment would work too. Just try not to drip this stuff into the oven or on the door unless you want your next loaf of bread to smell a bit piney.

I stayed close to keep an eye on it. The internet warned against letting it boil or smoke. (It did neither, so I didn’t need to decide what to do with it if that happened.)

Every ten minutes, I opened the door to stir the mixture.

n.b. This is the epitome of a “Don’t use anything you care about or wear anything you care about” kind of process. This stuff is sticky as all get out. To wit: you can use anything for mixing, but unless it’s made of silicone, you won’t be using it for anything else ever again, so choose wisely. I have a dedicated old silicone spatula that I use for studio things, but not for food. It’s a good idea to keep an eye out at charity shops and thrift stores for such things so you can have cheap ones you don’t care about. Today, I used disposable chopsticks that came with our last order of takeout Chinese food.

At first, the wax sat on the top of the mixture with a layer of thick, gooey, resin underneath. Stirring forced an emulsion to form and as we progressed, it stopped separating. After 30 minutes (three stirs) it looked like this.

I added a small dollop (random small amount) of tallow to the mix and stirred it in until the fat stopped floating on the surface.

Once the tallow was integrated, I upended the mix into my bus tub filled with water. We filled it from the tap as hot as it would get. By the time we used it, we wanted it to be about body temperature (90-100° F / 36° C). It came out of our tap at about 115° F (46° c) and cooled on the counter while the rosin and wax were in the oven. I measured it right at 98° F right before I dumped the wax into it.

The water acts as a heat sink, sucking the heat out of the mixture and forcing it to set. It also allowed me to reach in and use my hands to force it into a ball and begin to work it between my palms.

The center of the mass is still very hot, but keeping it submerged and working it carefully between my palms without thrusting a finger into it kept me from getting burned.

The water cannot be too hot, else it melt the wax mixture, nor cold lest it set the wax too quickly and crystals of rosin form.

I worked it and worked it, driving air bubbles out and watching for crystals to form. If small crystals form early, you can usually knead them out, apparently, but if big crystals form I’m told that tossing it back in the oven to start over with hotter water in the bucket is the only move.

If your hands get tired, try lacing your fingers together and using them as a fulcrum to just work the mixture between your palms. You can also work it on a sheet of silicone-impregnated baking parchment or a silicone baking mat. I wouldn’t work it on a countertop at any point.

Eventually, the mixture was too tough to work. Or maybe my hands were just too tired. The color was one homogenous yellowy-white and looked like the stuff Francis Classe showed me when I first approached him about shoemaking.

I wrapped it in some waxed paper and let it sit until it cooled down.

We will see tomorrow if it performs as shoemaker’s wax, but for now I get to rest my hands, have a beer, and read more about the mysteries of cordwainery… after I wash my hands about a million times. This stuff is STICKY!

Scott

Resources:

Reddit r/cordwaining

https://www.reddit.com/r/Cordwaining/comments/ydso19/my_experience_making_coad/

The Company of the Staple

https://companyofthestaple.org.au/making-coad-for-shoe-making/

and: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oH9O2OfQ2lY

Leatherworker.net “Making Coad Or Sticky Wax – The Easy Way…” (discussion)

https://leatherworker.net/forum/topic/69286-making-coad-or-sticky-wax-the-easy-way/

Other recipes

Harry Rogers

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5yIsZmz69-8&t=379s

Carréducker

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2zWPCj05EIo

Francis Classe, Raised Heels blog

http://aands.org/raisedheels/Techniques/coad.php

and: https://www.raisedheels.com/blog/?p=1149

An interesting side-digression on pitch and tar and archeological meanings and uses written by Wayne Robinson in his Reverend’s Big Blog of Leather: https://leatherworkingreverend.wordpress.com/2011/04/03/when-good-pitches-turn-bad/

Great!

LikeLike

[…] Perkins also has a recent post on his experience making coad. Scott works in US customary units, Staple and I work in an […]

LikeLike